Chekhov's Seagull

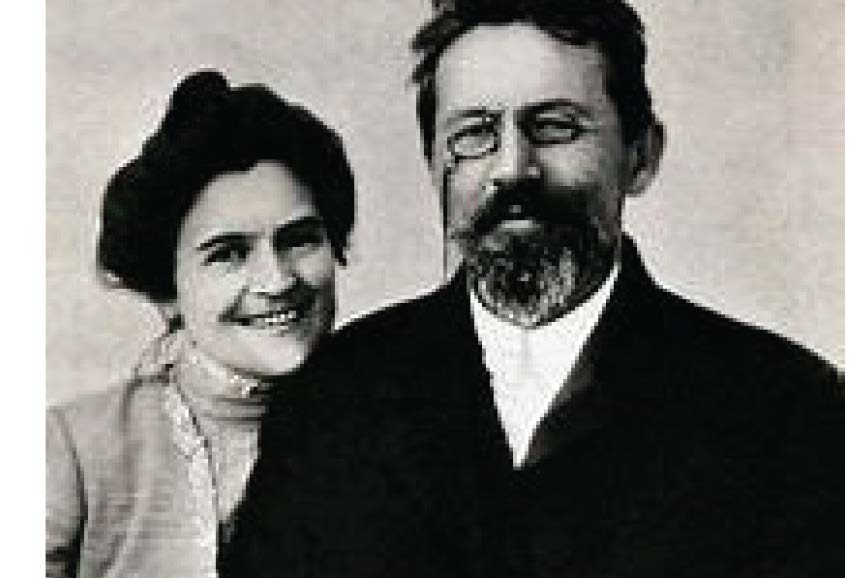

[Olga Knipper-Chekhova played Arkadina in Stanislavky’s

staging of The Seagull in 1898. She married Chekhov in

1903, a year before he succumbed to TB.]

[Young Chekhov, earned his degree in medicine, funding his way by writing comic stories. Much of his income went to

support his parents and siblings.]

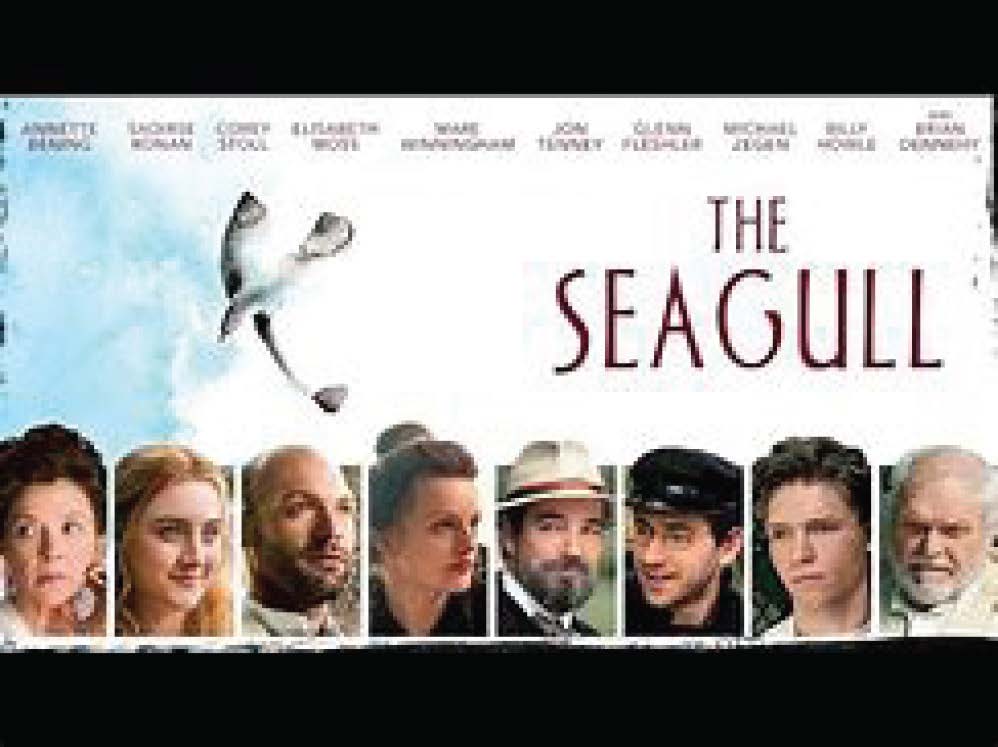

[This poster for the 2018 film shows the ensemble. Annette Bening as Arkadina dominates by virtue of the centrality of her role but also her star power. The production features the others equally, as was Chekhov’s intention.]

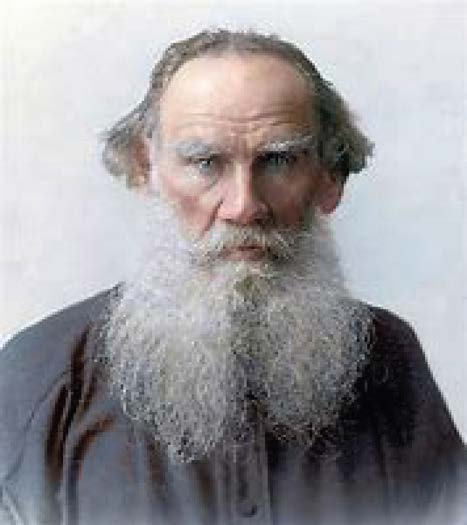

[Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) exchanged many letters

with Chekhov on art, philosophy, and Russia’s

prospects. In his later writings, Tolstoy sought to

preach his visionary Christianity, a didactic purpose

Chekhov rejected.]

[Chekhov corresponded with Maxim Gorky (1868-1936), offering him advice on the craft of writing. The two shared an interest in the lower social

orders and their suffering, though Chekhov did

not share Gorky’s socialism.]

[Frank Langella is Konstantin in the Williamstown Theater production.

He is dewy-eyed and childish, in rebellion against his mother’s world.

His play is absurd, a mockery of the new Symbolist theater Chekhov’s

realism rejects.]

[Kevin McCarthy plays the writer Boris Trigorin. He is a celebrity at thirty-seven but feels himself a hack writer, producing

stories on order and without passion or point. He is Arkadina’s toy, a childish man without a moral center.]

[Elizabeth Moss shines as Masha in the 2018 film. She is witty, and as an outsider has learned to see her world critically.

Masha opens each of the four acts, signaling Chekhov’s intent to make her weary sarcasm essential to the play.]

[Saoirse Ronan as Nina and Corey Stoll as Trigorin in Mayer’s 2018 film]

[Arkadina (Lee Grant) possesses Trigorin (Kevin McCarthy) in high melodrama as both play false in high theatrical nonsense.]

[Annette Bening as Arkadina is theatrical and

all but overwhelming in her force mixed with

painful uncertainty. She simulates emotion but

feels nothing but her own vulnerabilities. A resplendent

horror, she embodies Chekov’s ironies]

Anton Chekhov

Chekhov's Dark Comedy By Stephen Zelnick

Chekhov won fame as a writer for his short stories and for four plays that transformed theater.

The first of these, The Seagull (1896), continues to be produced yet remains a puzzle. Chekhov thought of it as comedy, but it is usually played as melodrama. It is, after all, a strange sort of comedy that includes so much pain and cruelty, ending with a suicide. Chekhov’s country landowners are comfortable enough, but with nothing much to do, their desires frustrated, and with no future. He was an outsider to that social order, a poetic interpreter of its decline. His art is restrained, compassionate in its mockery, as suits portraying a social order played out in history. The Seagull with its swirl of subtexts, as its world comes apart, speaks to us.

It failed in its opening performance in 1896 -- the audience all but hooted the play off the stage, and Chekhov declared he would never again write for the theater. Two years later, the play was performed by the Moscow Art Theater, and under the close direction of Konstantin Stanislavsky became a MAT mainstay. Indeed, MAT adopted the seagull emblem as its own.

Despite commercial success, Chekhov protested Stanislavsky’s realization of the play as melodrama.

Who was Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)? Although he moved comfortably among the elite artists of his day, Chekhov was born of peasant stock. His paternal grandfather had purchased his freedom and that of his family in 1840, only twenty years before the playwright’s birth; his father owned a small variety store in the port town of Taganrog on the northern coast of the Sea of Azov. When the business failed, young Anton was left to make his way on his own after his family, overwhelmed by debt, fled to Moscow. Chekhov recounted his own biography as follows:

That which writers belonging to the upper class receive from nature for nothing, plebeians

acquire at the cost of their youth. Write a story of how a young man, the son of a serf,

who has served in a shop, sung in a choir, been at a high school and a university, who has

been brought up to respect everyone of higher rank and position, to kiss priests’ hands,

to reverence other people’s ideas, to be thankful for every morsel of bread, who has been

many times whipped, … write how this young man squeezes the slave out of himself, drop

by drop, and how waking one beautiful morning he feels that he has no longer a slave’s

blood in his veins but a real man’s …

Young Chekhov embraced life with gusto. He loved telling stories, putting on plays, playing tricks, swimming, hiking the woods, and foraging for mushrooms. Growing up in a port town, he delighted in the variety of goods in the shops, and the colorful nationalities gathered at that bustling crossroad of fading empires. Throughout his short life (1860-1904), though plagued with illness, he never rested. He earned a medical degree, supervised the building of village schools, tended for free the sick among the peasantry, designed gardens and constructed houses for himself and family, and even traveled to Sakhalin Island in Siberia to study prison conditions and advance a program for reform -- and all that while penning 300 stories and a dozen plays. His medical career, he said, was his wife; his writing his mistress. Like Dickens, he was blessed with great talent and immense energy, and rocketed to fame from no place at all.

II

The Seagull presents an ensemble of characters, each highly marked by personal gestures, speaking styles, particular desires, and personal histories. Chekhov individualizes his characters so we recognize them quickly, and grasp their peculiarities. Still, we conceive of them within a group.

Chekhov proposes an art of sociability where we grasp the whole while delighting in the parts.

He invites his audience to stand aloof, above the drama, and take in this weave of lives and fates caught unaware in history’s web. We are among comfortable land-owners, drifting along in illusions.

They are a sorry lot, pitiable but laughable, inviting our amusement and, at times, our dread.

Chekhov asks us to hover above the action and look down upon it like gods, bemused and indifferent.

“Life is tragedy when seen in close-up and comedy in long shot--according to Charlie

Chaplin. Some say tragedy is for those who feel and comedy for those who think. Another insists tragedy is linear and comedy full of surprises. The comic perspective confirms our suspicion that we neither know what we are about, nor how to make sense of things. Chekhov tests our ability to get on without precise understandings. His characters cannot find their balance, and Chekhov makes sure his audience cannot either.

Several of Chekhov’s remarks about art help us grasp what he is about. In a letter he writes of his struggle to work outside the bounds of genre conventions: I should have liked to have been a free artist and nothing more -- and I regret that God has not given me the strength to be one. I hate lying and violence in all their forms -- the most absolute freedom, freedom from force and fraud in whatever form the two latter may be expressed, that is the program I would hold to … He resists having his writing serve a cause -- he is neither conservative nor liberal when he writes, and takes Tolstoy to task, as in The Kreutzer Sonata, for pressing his own ideas on his reader.

Chekhov’s ideal is to become “a writer whom the mob believes in (and yet) has the courage to say that he does not understand anything of what he sees. He wishes to become an amanuensis of life, taking notes with intelligence and grace, yet without imposing his urgencies upon his characters, or their fates. He resists answers when in life we

have only questions; for the writer the view that“ there are no questions, but only answers, can only be maintained by those who have never written and have had no experience of thinking in images. An artist who trusts in nature will resist the need to impose conclusions and views: “Nature is an excellent sedative. It pacifies -- that is, it makes one indifferent. And it is essential in this world to be indifferent. Only those who are indifferent are able to see things clearly, to be just and to work." An audience may insist that the work come to the point; the job of the writer is to resist that demand.

These comments help us understand how The Seagull, for all the pain of blighted marriages, both ugly and graceful deceptions, unfulfilled lives and dead dreams, and even suicide -- can be comedy. Chekhov puts it this way: “I have been cherishing the bold dream of summing up all that has hitherto been written about whining, miserable people." While writers often insist their characters be saints or villains, it should be “enough that all men are sinners." Chekhov insists: “My business is merely to be talented == i.e., to know how to distinguish important

statements from unimportant, how to throw light on the characters, and to speak their language."

His task is not to judge them but to portray them, in all their inconclusiveness, and to resist forcing an ending upon them.

Chekhov mocks the bourgeois need for happy endings. Having grown up amidst the peasantry, he can write, with some wickedness: “The bourgeoisie is very fond of so-called practical types and novels with happy endings, since they soothe it with the idea that one can both accumulate capital and preserve innocence, be a beast and at the same time be happy." Life observed by the outsider, who makes his way by his wits and by seeing things as they are, invites a different sensibility.

Chekhov’s program for art explains his laconic style and habits of indirection, which lends his work a crisp modern feel. In The Seagull most actions -- including two suicide attempts and a tortured liaison -- occur offstage and are acknowledged in passing. He records what he imagines he would hear and leaves it to the reader’s alertness to catch the subtext. My favorite example occurs in his story, “Lady with the Small Dog". Gurov, his central character, is comfortably married with two children, living a conventional life as a bank official. He has an affair with a young woman on vacation and is surprised by the meaning this has for him. He imagines this as common, and mentions it to a fellow club-member:

One evening, coming out of the doctors’ club with an official with whom he had been playing cards, he could not resist saying: “If only you knew what a fascinating woman I made the acquaintance of in Yalta!" The official got into his sledge and was driving away, but turned suddenly and shouted: “Dmitri Dmitritch!" “What?" “You were right this evening: the sturgeon was a bit too strong!"

What is not said is: “you need to understand we do not talk of such things!" Writing for the stage, this indirection serves Chekhov’s comic purposes perfectly. Masha’s opening remark about mourning for her life is one of several bits of bitterness repurposed as humor. Asked whether she has married, she says she has married, and then, if she is happy, she repeats, “yes,I am married."

Chekhov’s evasiveness fits his temperament. He says of himself: “The fire burns in me slowly and evenly, without suddenly spluttering and flaring up … this is why I commit no particular follies nor do anything particularly wise.-- He contains his passions and proceeds with care.

He writes to a colleague: “to my mind you have not enough restraint. You are like a spectator at the theatre who expresses his transports with so little restraint that he prevents himself and other people from listening." Elsewhere he advises writers to stand aside from their enthusiasms:

“You may weep and moan over your stories, you may suffer together with your heroes, but I consider one must do this so that the reader does not notice it. The more objective, the stronger will be the effect." To sum up: “it is better to put your color on too faint than too strong."

Little surprise, then, that audiences and directors, miss what Chekhov is about. He requires ironic distance with subtleties of tone. Chekhov’s indirectness and economy may leave playgoers at sea, in a staged world as complex as their own. When Arkadina parades her youthfulness, she is struggling to sustain her confidence. The more she asserts power, the sadder she seems. She protests she loves her son, but refuses to buy him a coat. Her kind words to Nina regarding the young woman’s acting skill seem generous but mask resentment at her youth.

III

Another feature of The Seagull is that writing itself is a topic of constant conversation. Konstantin’s play is performed in Act One and again referenced in Act Four. Arkadina calls it decadent, Nina complains there are no characters and no movement, Dorn finds it lacks purpose and direction. Much as we would like to applaud young Kostya’s effort, these dismissive judgments are too kind -- especially when we consider Chekhov’s art of layered implication, of restraint and muted colors. Instead, Kostya’s play is a jumble of images groping for significance, and Nina’s performance unfocused. Kostya’s play reaches beyond the quotidian but into a cosmic soup of murky images:

Like a captive in a dungeon deep and void, I know not where I am, nor what awaits me. One thing only is not hidden from me: in my fierce and obstinate battle with Satan, the source of the forces of matter, I am destined to be victorious in the end. Matter and spirit will then be one at last in glorious harmony, and the reign of freedom will begin on earth. But this can only come to pass by slow degrees, when after countless eons the moon and earth and shining Sirius himself shall fall to dust. Until that hour, oh, horror! horror! horror!

Chekhov mocks the vogue of Symbolist theater, emerging from Paris and Belgian playwright

Maurice Maeterlinck (1892-1949).

This symbolist revolution requests more plays about schoolmasters and embraces the romance of underwater caves and remote mountaintops. Chekhov’s spoof of Symbolist theater rejects characters, leaving vast abstractions to play out the fate of all things living, 200,000 years in the future. Konstantin’s revolution is amateurish and bombastic. Arkadina protests this foolishness, and even Nina complains of its vacancy.

Dr. Dorn is moved by the play’s imagery, but his romantic comments about art are not Chekhov’s. Dorn proposes: “A work of art should invariably embody some lofty idea. Only that which is seriously meant can ever be beautiful." Followed by “if I should ever experience the exaltation that an artist feels during his moments of creation, I think I should spurn this material envelope of my soul and everything connected with it, and should soar away into heights above this earth." This idealist nonsense should evoke laughter, and Chekhov supplies the punchline, when Konstantin responds: “I beg your pardon, but where is Nina-- Medvedienko supplies another deflating remark when he requests plays about schoolmasters and their low pay.

Chekhov excelled at prose fiction, and Trigorin provides a mocking commentary on the grinding labors of the writing desk. Trigorin, a driven workman, collects phrases in a notebook for re-weaving into the fabric of stories. Explaining his procedure to the star-struck Nina, Trigorin observes a cloud shaped like a grand piano, jots down the moment in his notebook, and explains he may find it useful in some future story. Dorn’s effusion is laughably overwrought, and Trigorin mechanical assemblage of bits and pieces recalls Swift’s workshops of Laputa. In Act Four Kostya labors to evoke an atmosphere of midnight. He complains that Trigorin has the right formula while he is forced to scurry about unable to fix the mood out of a grab-bag of images. Kostya is suffering, and we shouldn’t laugh, but Chekhov makes his characters’ frustrations ridiculous.

IV

What sort of play is The Seagull? The curtain opens and Masha is talking with an ardent

young man. “Why do you dress in black?" asks her witless suitor. “I am in mourning for my

life", she answers. This is somber but witty; in the 2018 film, it is pitched for a Woody Allen laugh. Next, Kostya and Nina appear, an adorable couple, but Nina dodges away from Kostya’s embrace. We expect romance and poetry, but Nina loves the lake and not Konstantin:

“NINA. this lake attracts me as it does the gulls. My heart is full of you. [“you're here is the lake … She glances about her.] KOSTYA. We are alone. NINA. Isn’t that someone over there?

KOSTYA. No. [They kiss one another.] NINA. What is that tree? KOSTYA. An elm. NINA.

Why does it look so dark? KOSTYA. It is evening; everything looks dark now.--

Nina’s evasive questions are comic, and Kostya misunderstands this mockery of a love scene.

Medvedienko loves Masha, Masha loves Kostya, Kostya loves Nina, and Nina loves Trigorin

recalling the mad comic confusion of Midsummer Night’s Dream.

In the darkening evening, singing drifts across the lake, and Arkadina recalls years earlier, when “we had music and singing on this lake almost all night. All was noise and laughter and romance then, such romance!--And Dr. Dorn remarks as the Act ends: “And how much love there is about this lake of spells! Nina, a wide-eyed innocent, raised on the lake’s shores and mistress of all its islands and coves, is held captive by her brutal father and wicked step-mother who have robbed her of her mother’s legacy. Nina, the seagull, is the spirit of this magical place.

Trigorin revives his worn spirit, as in allegory, by fishing the lake. Here Kostya presents his play, a device to lure Nina and to punish his mother for defiling the memory of his dead father. With such magical associations, The Seagull seems anything but naturalistic. But the characters face troubles like our own, and they speak everyday language, even to dreariness. Medvedienko, Masha’s impoverished school-master suitor, believes in counting every penny; Shamaeff, the practical estate manager, recalls long-gone performers with tiresome anecdotes; Paulina, his wife, pesters Dr. Dorn, the man she has always loved; old Sorin, the retired Councilor, cannot leave off tallying his regrets in life. The setting may suggest fairy-tale but we recognize this complaining as that of neighbors and family-members in life’s decline to exhaustion.

Another set of characters cultivate lively dreams. Dr. Dorn, once “irresistible" to women and the object of Arkadina’s romance, is moved by Kostya’s play as it gropes towards the “Oversoul"

He is a fading spirit, congenial but bored, and with an amateur’s half-formed judgments about art and philosophy. Dorn aims at high-minded notions. His instruction to Kostya is heart-felt but long out of date.

Arkadina and her lover Trigorin, unlike the others, enjoy successful careers. They are celebrities, well-known in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Kiev. However, their aspirations are bourgeois; they are absorbed in the business of art and inspired solely by stardom:

ARKADINA. Could you believe it? I am still dazed by the reception they gave me in Kharkoff … The students gave me an ovation; they sent me three baskets of flowers, a wreath, and this thing here. [She unclasps a brooch from her breast and lays it on the table.] … I wore a perfectly magnificent dress; I am no fool when it comes to clothes.

In the presence of Masha and her mother, Paulina, both drab and overlooked, these remarks are cruel, and Arkadina, absorbed in self-praise, ridiculous.

Arkadina, in her forties, boasts her self-importance, and fears growing old. Trigorin, her lover, is ten years younger, and though a celebrity, fails as an artist, pursuing ambition without purpose or passion. Though praised in the press as another Turgenev, Trigorin has no joy of creativity: “I am finishing another novel, and have promised something to a magazine besides. In fact, it is the same old business." Earlier Trigorin admits to Nina that writing has become tedious, collecting

observations and fine phrases and fitting them into worn-out dramas:

“TRIGORIN [to Nina}. What success have I had? … as a writer, I do not like myself at all.

The trouble is that I am made giddy, as it were, by the fumes of my brain, and often hardly know what I am writing … I love my country, too, and her people; I feel that, as a writer, it

is my duty to speak of their sorrows, of their future, also of science, of the rights of man, and so forth. … I see life and knowledge flitting away before me."

The remark and so forth--signals Chekhov’s mockery. Nina shares these ludicrous notions:

“NINA. If I were a writer like you I should devote my whole life to the service of the Russian people, knowing at the same time that their welfare depended on their power to rise to

the heights I had attained … For the bliss of being a writer or an actress I could endure want, and disillusionment, and the hatred of my friends, and the pangs of my own dissatisfaction

with myself; but I should demand in return fame, real, resounding fame!"

Masha also aims to reach beyond the everyday. Unlike Trigorin, the celebrated author, she is verbally clever; she is also an alcoholic, drowning in self-pity. After several shots of vodka, Masha unleashes another of her dark comic remarks: MASHA [to Trigorin]. Send me your books, and be sure to write something in them; nothing formal, but simply this: -- To Masha, who, forgetful of her origin, for some unknown reason Konstantin (Kostya), is vaguely a revolutionary. He has been dismissed from the university and aspires to avant-garde forms of theater to replace the tired formulas and the money interests and

coteries of stardom. Nina, a free spirit, is unschooled and starry-eyed, lacking in discipline, and overwhelmed by emotion. The pair is dogged by misfortune, but their poisoned fates are their own doing. If Russia’s future depends upon the middle classes and the rebellions of their youth, there is little hope for it. Their “sturm und drang" is the proper object of ridicule, for a man of Chekhov’s history, the peasant outsider who forges a life for himself.is living in this world.’ -- Dorn and Masha, likely Dorn’s biological daughter, express, in stronger form, the wish in all the characters to reach beyond life’s tedium … a doomed wish haunted by inflated memories and dreams far out of reach.

V

The Seagull is episodic, with each Act supplying several well-crafted scenes, gathered like expert tile-work. Act III offers one of the best, when Trigorin, infatuated with Nina, comes to begaging Arkadina to be released temporarily from their relationship to pursue a dalliance with this fresh 19-year-old:

ARKADINA. Am I then so old and ugly already that you can talk to me like this without

any shame about another woman? [She embraces and kisses him] Oh, you have lost your

senses! My splendid, my glorious friend, my love for you is the last chapter of my life. [She

falls on her knees] You are my pride, my joy, my light. [She embraces his knees] I could

never endure it should you desert me, if only for an hour; I should go mad. Oh, my wonder,

my marvel, my king! TRIGORIN. Someone might come in. [He helps her to rise.] ARKADINA.

Let them come! I am not ashamed of my love. [She kisses his hands] My jewel! My

despair! You want to do a foolish thing, but I don’t want you to do it. I shan’t let you do it!

[She laughs] You are mine, you are mine! This forehead is mine, these eyes are mine, this

silky hair is mine. All your being is mine…. Oh, my very dear, you will go with me? You

will? You will not forsake me? TRIGORIN. I have no will of my own; I never had. I am too

indolent, too submissive, too phlegmatic, to have any. Is it possible that women like that?

Take me. Take me away with you, but do not let me stir a step from your side.

The translator’s “I shan’t let you do it" gets the farcical measure of this stagey emotion just right.

What follows tells the tale, just in case we missed it:

ARKADINA. [To herself] Now he is mine! [Carelessly, as if nothing unusual had happened]

Of course you must stay here if you really want to. I shall go, and you can follow in recoga

week’s time. Yes, really, why should you hurry away? TRIGORIN. Let us go together.

Both the 1968 Lumet film and the 1975 PBS video, take this melodrama, with its worn

gestures, seriously. The 2018 film underscores Chekov’s mockery in this. In the next scene,

we find neither meant what, in their high-blown way, they had said.

VI

Act IV moves two years into the future, indoors and away from lake and woods, and lawn and

verandah of the previous acts, as wintry cold arrives. Sorin is dying, and his sister Arkadina

returns from Moscow to attend him. All the characters are stuck in a dismal cycle of repetition

-- the comedy of Waiting for Godot -- in a dreary wasteland of the all too familiar.

Act IV is a grim sit-com. Each character has tag-lines, made comic by their mechanical regularity.

As the act opens, Masha still calls for Kostya, Medvedienko begs for a horse, and his

father-in-law complains he has no horse to lend. Paulina longs for loving attention. Masha still tries to convince herself she can pluck love “from her heart by the roots". Sorin calls for palliatives and Dr. Dorn mocks him. Sorin regrets his failure to become a writer, an orator, or a husband. Shamraef bemoans the diminished world of the stage. As the group settles down to play Lotto, Arkadina complains of the game’s monotony, even while Kostya’s fate is settled in another offstage suicide. The Lotto wheel replaces the Medieval Wheel of Fortuna but also endless motion without progress.

Arkadina again boasts of her reception by adoring students, of how well she dresses, while

Shamraev praises her youthful appearance. Trigorin goes on about fishing, and Dorn offers the

same advice to Konstantin about play-writing. Arkadina reminds us again, as in Act I, that she

has read nothing her son has written. As in the love duet between Konstantin and Nina in Act I,

Nina fears someone coming; Konstantin again sees himself standing in her garden “like a beggar"

they recite again lines from Konstantin’s play, Nina speaking them as Kostya again mouths

them. The result is that comic irony when the audience knows what the characters fail to recoganize -- suffering monotony, unaware of the source of their disease, and longing to break free of it.

In case we have missed this grim monotony, two of the play’s grand speeches reinforce the theme.

Nina counsels Kostya:

“for us, whether we write or act, it is not the honor and glory of which I have dreamt that

is important, it is the strength to endure. One must know how to bear one’s cross, and one

must have faith. I believe, and so do not suffer so much, and when I think of my calling I do

not fear life."

Life requires the strength to submerge oneself in its monotony? Despite language advising bearing ones cross, there is no suggestion of a higher power or greater cause we owe this sacrifice. Can Chekhov be teaching us that strength comes from plodding at ones calling and being absorbed in it -- as in Nina’s upcoming bookings in dreary provincial towns, with dull audiences and lewdmbusinessmen? Nina’s speech is “theatrical", but carries no weight or conviction; Blythe Danner in the PBS version adopts method mumbling to blot out its inanity.

The last words return to Konstantin’s silly play:

--all, all life, completing the dreary round set before it, has died out at last. A thousand

years have passed since the earth last bore a living creature on its breast, and the unhappy

moon now lights her lamp in vain. No longer are the cries of storks heard in the meadows,

or the drone of beetles in the groves of limes. The Lotto players call out the numbers and cover their cards, in mock excitement at the game, in this pastime where the stakes mean nothing.

For Viewing

Three fine performances of “The Seagull" are available online:

Sidney Lumet’s 1968 film (James Mason, Simone Signoret, Vanessa Redgrave, David Warner, and Harry Andrews) --- shot at a distance, Lumet misses the intimacy of the exchanges;

Signoret is older here, which suits the part; Mason, however, is too old for Trigorin, a younger

kept man. This version is reverent and misses the parody, irony, the comic hypocrisy and dark irony.

PBS “Theater in America" is a video of the Williamstown Festival Theater Presentation (Kevin McCarthy, Lee Grant, Blythe Danner, Frank Langella, and Olympia Dukakis) -- this is an in-doors production where the camera is free to range. Langella is the most weepy of the Konstantins, a boy in his enthusiasms and overwhelmed in toddler rebellion; when his mother rejects him, you feel his infant abandonment; Lee Grant as Arkadina -- commandingly beautiful and, voluptuous, but uncertain -- works well; McCarthy is the surprise, handsome and virile, morally adrift, and hilariously costumed like a birthday gift. Dukakis’ mad assault on a floral bouquet -- the visualization of the phrase “tear out love at the roots" is the one laughing

moment.

Michael Mayer’s 2018 Film (Corey Stoll, Annette Bening, Saoirse Ronan Billy Howle, Bryan Dennehy, and Elizabeth Moss) catches the comedy in its several modes. Bening accentuates Arkadina’s power-mad uncertainty with every quirk, down to her penny-pinching and cruel defensiveness; Billy Howle (a young Olivier in looks) retreats into adolescent peevishness, pounding his piano madly (impossibly demanding Rachmaninoff and Scriabin pieces, shaking his head in stagey transports of emotion); but the wonder of this production is Elizabeth Moss as Masha, a figure largely ignored in other productions, with quirky intelligence and superb comic timing (recalling Wallace Shawn in Louis Malle and Andre Gregory’s film Vanya on 42nd Street).

Mayer’s production features the servant class -- in Russia, recent serfs, like Chekhov’s family -- peeking out from behind the scenery to mock their masters, in sly and rascally ways. “Don’t I look just as I did at fifteen", sings out a matronly Arkadina as she twirls, a bit off-kilter -- and as a serving-girl smirks directly to us into the camera. The film’s final scene catches Arkadina as she hears of Kostya’s death, frozen in profile in Gloria Swanson’s theatrical grimace from Sunset Boulevard. It is possible that Mayer has played a post-modern trick on Chekhov; it is

likely Chekhov was already there.

More Chekhov:

Vanya on 42nd Street, Louis Malle and Andre Gregory’s 1996 film Three Sisters, Laurence Olivier, with Joan Plowright, Jeanne Watts, and Derek Jacobi, 1970.

The Cherry Orchard, Michael Cacoyannis, with Alan Bates and Charlotte Rampling, 1999.

The Autobiographical Writings: Diary, Letters, Reminiscences, and Biography, edited Constance Garnett.

Complete Plays, Translated by Laurence Senelick with copious notes, 2006

Reading Chekhov: A Critical Journey, Janet Malcolm, 2006.