[This youthful portrait captures some of Storni’s verve and good humor. In her teen years, she hoped for a life in theater. While that hope went unfulfilled, her poetry often shows a knack for the dramatic turn and crisp vivid dialogue.]

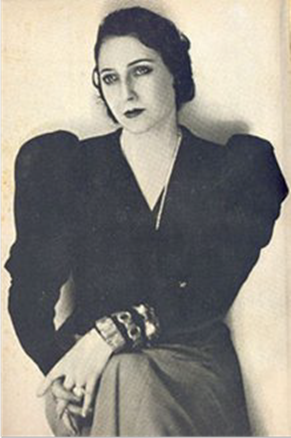

[Juana de Ibarbourou (1892 - 1979): was a celebrated Uruguayan poet and Alfonsina’s good friend. More at home in the Latin world than Storni, she wore her elegance and beauty well. She could easily serve as the model for 'Dolor’.

[During Storni’s lifetime, Argentina enjoyed a formidable economy, in 1910, the seventh wealthiest in the world.

Buenos Aires benefitted from being a major port and Argentina’s political, commercial, and cultural center. A third of its urban population was European.

Storni lived in Buenos Aires during the height of tango and its sensual allure. Carlos Gardél (1890- 1935), the great Argentine composer and performer, earned world-wide fame in those years. Storni delighted in singing popular tango songs till dawn in local bars..

Though on a smaller scale than the American cities of the United States, in South America, Buenos Aires in 1930 boasted splendid buildings, elegant cafes, and broad boulevards.]

[In several photos, Alfonsina is blonde and obviously European.]

«Alfonsina y el mar» es una zamba compuesta por el pianista argentino Ariel Ramirez y el escritor Félix Luna, publicada por primera vez en el disco de Mercedes Sosa Mujeres argentinas, de 1969. Image Credit: Falsia de Mar of the Union Hispano Americano

[This monument to Alfonsina at Playa la Perla, Mar La Plata, Argentina shows her as a female warrior, an appropriate depiction of her accomplishment.]