Shiva by Ian Fisher

The party and Mandarin duck were Nessa’s epiphanies, and the cash came from R.: his guilty conscience, no doubt. Kudos for logistics and execution, however, belonged to Ailbe, whose name was pronounced Allbay; only she could have pulled it off. In 2028, Ailbe, thirty-three, was controlling shareholder and chief executive officer of a Dublin-based tech conglomerate in the business of human artificial intelligence and, by dint of strategic alliance with a Hollywood motion picture studio, 3D avatar design.

This was the year of the 75th birthday of Nessa’s husband, Ira. Although the couple no longer lived together, they remained contra mundum. Nessa over coffee in South Kensington of a winter’s day--unveiled to Ailbe her vision for Ira’s birthday banquet:

I’ve been thinking about this for a decade. I made up the guest list from desktop photos on his MacBook Air. But is it even possible?

Believe it or not, said Ailbe, it is: Orson Welles meets HG Wells. Do you have any special requests?

Three things, said Nessa, I’d like all guests, including Ira, to dress formally. I’d like a pet duck waddling around the floor. And, outside, I’d like it to start snowing after Ira arrives and continue snowing until he leaves. Like Pete Hamill’s Snow in August. We should also talk about how to get Ira to show up.

Do you have something in mind? said Ailbe.

In the mid-nineties, Nessa said, Mom treated the entire family to Ireland, where we stayed at Ashford Castle. Ira and my niece fished Lough Corrib with a guide. According to Ira the guide was grandson of a former groundskeeper for the Guinness family. Ira never told me his name, but once remarked that there was a nurse with the same last name in a James Mason / David Mamet movie and the name ended in a vowel. Do you think you could track him down, and entice him to fish with Ira for a few days?

Brilliant, said Ailbe, sounds fab!

What else do you need from me?

I would need, said Ailbe, the list of guests, their ages, Ira’s shoe and hat sizes, and a credit card account. If I think of anything else, I’ll text you.

You did say formal dress.

O, said Nessa, I expect Ira would just wear his Hanna Hat of Donegal tweed we bought in Newport in the mid-eighties.

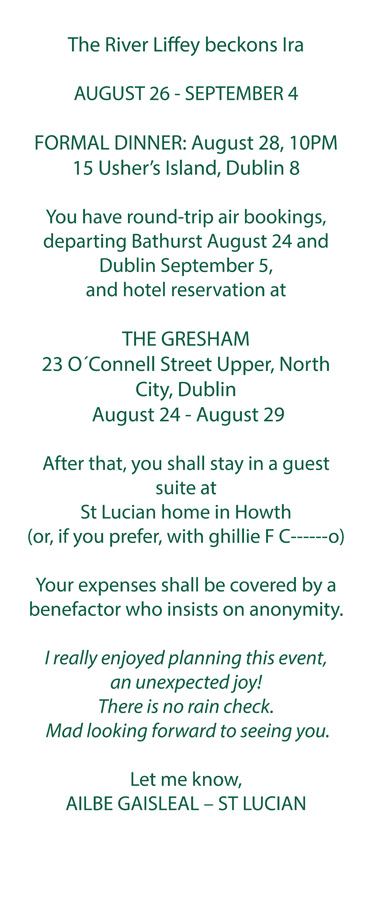

And so the engraved invitation below (along with Ailbe’s handwritten mobile number, email address, and home address in Howth) arrived that summer at Ira’s fishing cabin in New Brunswick, during an aberrational early first season run of Salmo salar.

If Ira had known the identity of his anonymous benefactor, he might have told R., in the happy phrase of a le Carré character, to shove it up his smoke and pipe it.

But this was an invitation not even Ira could decline.

Living with R. in Belgravia, Nessa continued to imagine and coproduce Ira’s first ever surprise party. After all, although she knew Ira abhorred parties, what was the risk? The Jesuits had blessed her thirty-eight-year marriage to Ira, father of her only child, but Ira was living alone in his native Canada. Projecting, Ira had taken to calling Nessa: My dear little runaway.

Nessa worried about Ira and prayed for him every day. He was tilting at windmills and not abiding human contact, except with his Miramichi guide. Otherwise, Ira’s shrinking cohort--with whom he interacted only by phone or laptop-comprised Nessa and son Rónin, Ira’s sister in Mon-treal, and two old far-away friends. He presented with paranoia about anti-Semitism and personal health; obsessions with sexual frequency, nostalgia, and death; compulsive viewings of The Sorrow and the Pity; and myriad other neuroses. He had no small talk.

For many years, Ira himself had feared the fate of From the Terrace’s protagonist Raymond Alfred Eaton: prematurely in retirement, friendless, and relegated to the humiliating rôle of factotum.

Ira’s social isolation had begun with the retirements of his business partner and most of his merger-and-acquisition clients, and continued in 2018 with the deaths of his parents and with Rónin’s moving away from home to pursue a PhD. When COVID came, Ira’s life hadn’t changed much at all; as if no longer successfully alive, he had severed the bond of community.

Hello, Mr Fielderer, said Dolly, welcome to Dublin.

Ira was vexed by the three-syllable mispronunciation of, and extra r in, his name: it evoked for him R.’s surname. Dolly also gave an extra syllable to the town, reprising a popular rendition of The Rocky Road to Dublin.

--Hello, he said.

--How was your crossing?

--Grand, said Ira, I’ve almost adjusted to the time zone.

--I have a crow to pluck with you, said Dolly.

--What is it? he said.

--You nevehr called! I waited by the telephone for houhrs, counting by fives.

On the table’s handmade Irish lace and linen tablecloth stood three candelabras, each with six lit maple-scented black candles, and two crystal square decanters. Behind the three seats on the top side of the table (the side to the right of the head of the table, the chair reserved for Ira) was a fireplace, blazing seasoned eucalyptus flown in from San Francisco, with antique rass instruments on both sides of the hearth.

Framed above the mantel, an oil-on-canvas painting: an overcast snowy dusk on the east side of Montreal: a goalie and four other boys--two wearing red, white, and blue Canadiens jerseys and all wearing tuques--playing street hockey, none of their faces visible; power and telephone lines from poles connecting the red-brick and wooden tenement buildings, with their outside balconies and spiral metal fire escapes, on each side of the lane; and three cars parked haphazardly on one side. For Ira, the painting evoked the alleyways of his father’s boyhood. And two of his father’s favourite aphorisms:

--Childhood is the happiest time in life.

--The best places to live are where snow falls

Behind the three seats on the other side of the table were a large upholstered peacock blue chair and adjacent sideboards laden with silver serving dishes. A waiter stood at attention in front of each sideboard.

The floor was hardwood cherry, polished with beeswax. On the emerald paisley Persian rug, behind Ira’s chair a Mandarin duck moved this way and that, of orange and green and purple and black-white, fluttering his feathers and quacking, a long way from New York’s Central Park Pond.

Ducks had been romantic avatars for Nessa and Ira: for decades, he had bought depictions of ducks for her in San Juan, Palm Beach, and Montreal, and Nessa had reciprocated from London.

Ducks of wood, silver, bronze, pewter, crystal, amethyst, porcelain, lapis lazuli. A visit to one of the homes that Ira and Nessa shared over the years was like a trip to a museum of miniature ducks, presented on mantelpieces of fireplaces in New York, Deep River, San Francisco, and Palm Desert. A green and blue duck with red and yellow beak had even adorned the foreground of a framed water-colour of two tigers in repose by a stream in Rónin’s first apartment in Goleta, California.

Ira had not eaten since room service stirabout. So, in the last ninety minutes of his 75th birth-day, he sampled the gamut of the bespoke menu: salad with chunks of iceberg lettuce, heirloom tomatoes, and pepperoncini in balsamic vinaigrette, stuffed turkey with thick giblet gravy, green bean casserole, marinated mushrooms, green pimento olives, capers, and celery, and-for dessert-a small slice of tarte au sucre and fudge-iced brownie baked according to the recipe of Nessa’s Mom. Ira’s tipple was Guinness's Extra Stout.

Not a single one of the seven other guests was as hungry or as thirsty as Ira. And that made perfect sense, of course, since the seven others at table were 3D avatars of Ira’s favourite authors from among the dead.

There came a time when Ira clinked his half-empty glass with the blunt side of his last knife. --Lady and gentlemen, Ira said, I would like to dedicate some words, which I’ve been fretting bout for some time, to someone dear to me who died.

--Get up on your hind legs, old dahrling, said Cliff, and be as impertinent as the occasion demahnds.

--Well, you know, Norm said, he should really remain seated. It’s a tradition of our mythology.

Playing pianissimo was the sombre melody to Bantry Girls Lament. Ira cleared his throat, and began reading from seven pages handwritten meticulously on loose-leaf Midori cotton paper in vintage Sheaffer fountain pen ink of peacock blue, the colour of Pinocchio’s bowtie in the 1940 animation:

He evidenced the cool of Dean Martin, the intelligence of Noam Chomsky, and the heart of Don Quijote de la Mancha. In his time, which lasted a long time, this gentle man could engage as easily with heads of state, stars of stage, and captains of commerce as he could with doormen and drivers and stevedores. He evoked urban class, from an era of cigarettes, nightclubs, and hats.

--Ahh, splendid night, said Will in a whisper to Clevie, seated to Will’s right, this is a splendid summer night. It is a night where The Dahgda in emerald cape rides Ocean over the slieves to the Unshim River in Corahnn.

--I do not share your optimistic transcendence, said Clevie, adjusting the frame of his tinted glasses, dreams you know are what you wake up from. Life is bad luck, failure, brooding, and profound depression. So, it’s not easy; things do not work out. The fact is, that time is short and the water is rising.

. . forcing us to scramble for accommodations when the hotel relinquished our rooms to the travelling entourage for The Beach Boys. After a secretary interrupted that afternoon’s negotiations with news she had been able to track down and secure a single room, I breathed a sigh.

--I discovered the bluezh, said Freddie to Norm, on Freddie’s left, listening to Nobody in Town Can Bake a Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine, which I bought for a nickel, and I played it twenty-two straight timezh. You sing the bluezh cuzh thatzh a way of understanding life.

--Well, you know, Norm said, you gotta earn the right to sing the blues, uhh? They fit in when-ever the heart is full enough and, you know, the heart is willing. It’s not really my tradition, but I love it.

. . . And because he expected the work to be perfect, he expected you to stand your ground in its defence. That is merely one of the myriad lessons he taught me and others privileged to know him well. He was self-assured, equal parts strict and fair, and he led with excellence. He had cachet; he had panache; and, underneath all that style, he,

Murray, sotto voce, complimented Norm on his famous blue raincoat and small-brim wool-felt fedora: Snazzy, what I used to call snazzy. Heh-heh. People still say snazzy?

--Thank you very much, said Norm, I think they do.

--Norm, from Norman. English, probably, or possibly German, said Murray, how’s your ancient German? Northman? Norseman? Then Old French. Some of your namesakes settled about twenty kilometres east of here in Howth.

--First we take Manhattan, said Norm, then we take Dublin.

. . and join me in this toast of words written by the enigmatic scribbler who immortalised this very House of the Dead

No sound of strife disturb his sleep!

Calmly he rests: no human pain

Or high ambition spurs him now

The peaks of glory to attain.

--Ahh, splendid, Ira, said Will, a lapidary encomium of inestimable grandeur.

Earlier, at the rising of the moon, Nessa stood seven hundred metres east away, along the Liffey in Merchant’s Quay, lighting candles at Adam and Eve’s. But her mind, too full of memories, was 1,240 kilometres and forty-six years away. ]

---This is Ira’s party, not mine, she thought, and besides, I’ve booked myself into The Gresham too.

Well past midnight, after all other guests had faded away (Ira himself had overheard at least eleven good-nights and several solicitous let’s-do-this-agains), Norm, Ira, and Dolly lingered at table.

--You know, Ira, said Norm, I was a great fan of your Dad’s. Ever since St Patrick’s Day 1955. He was an embrocation against boredom.

--The Richard Riot, said Ira, part of Dad’s legend. He was a great fan of yours too, you know, and because of that, around the time of my bar mitzvah, I became a fan of your work as well.

--I always wanted to be paid for my work but I didn’t want to work for pay, said Norm, there are certain private obsessions that really determine what your life is. A lot of mine was concerned in turning out a certain standard of work. It was fitting that my friend Gabriel performed at your Dad’s funeral.

--Yes, Ira said, but did you hear that we asked Gabriel to sing Hallelujah and he refused: he said it was not liturgical.

--That’s unfortunate, said Norm.

--Ira, said Dolly, I have another crow to pluck with you. I didn’t much caihr for one of your guests.

--Which one? said Ira.

--The one in the wheelchair, she said, Cliff.--Why not? he said.

--The old four-eyed rogue didn’t engage with me before you arrived. And during dinner, of course, he sat at the tap end. But when he bade me good-night, he tilted his head, licked his lips from left to right, and slurred: I suppose a fuck’s out of the question?

The beginnings of a memory bubbled up in Ira’s brain: a post-midnight stroll, an improvisation, in Z-- rich in the rare auld times with Nessa, who on that night could have been the twin of Graciebird Kelly in Hitchcock’s REAR WINDOW. Ira stood up and said:

--Well, it’s been marvellous. Thank you both for coming. But I have a breakfast meeting at The Gresham in a few hours with my Howth hostess and my favourite ghillie. I was led to believe this was a fishing trip; that’s how they got me here. About three decades ago, I spent a cold rainy day lake-fishing with him; five years later I fished with him again, that time on a river. He invited me to stay with him the next time I visited. And this is the next time.

--Good-night, Ira, said Norm, tight lines.

--Good-night, said Ira, I doubt that we shall meet again.

--O, do you really think so? said Norm, how little you know of spirituality. But it’s clear that it’s only catastrophe that encourages people to make a change.

--You have a lot of wisdom to share, said Ira, are you a religious man?

--I have no religious aptitude, said Norm, I don’t have that gift: I failed as a monk.

Thank G-d. -- Good-night, Dolly, said Ira.

--Beannacht libh, Ira, said Dolly.

Moments later, Ira stood in the ground floor foyer of the four-storey dim grim Georgian. From upstairs, he heard music. Gazing up, he faced the shadowed figure of Dolly, her left hand on the banister of the landing. Wistful. Winsome.

Norm was playing the old square piano in the back room and singing of love: it sounded like a lay funeral hymn. In a voice of gravel and green, Norm mourned about old ghosts meeting on a quiet street.

==Dolly, shall we? Ira interrupted the lamentation from the foot of the staircase, let’s you and I walk out in the snow along by the river and through Phoenix Park.

Dolly’s hazel-emerald eyes glittered as she descended towards Ira.

He turned away and opened the inner door to the vestibule and took several steps towards the front door. Under the entryway bench, a pair of galoshes. Ira opened the street door to the pure cold air of early morning, and waited for Dolly to step outside in front of him.

An ebony cab drawn by two Friesian stallions with black plumes and reins grasped by an old coachman in silk top hat and black uniform, flanked by two lanterns, was parked at the curb, blocking the droichead: on the carriage side, in gilt lettering, Willoughby & Son. The coachman looked down from his seat, tipped his hat, and said:--Room for just one inside, Sir.

Then, of a sudden, as Dolly crossed the threshold a snowflake touched her simulacrum and she disappeared. And Ira was alone.

Ineffably happy--from memories of Dickens’s Dr Alexandre Manette recalled to life, and from sighting the corporeal Nessa lingering under a snow-tufted lamplight in her buttoned and belted ivory wool/cashmere coat--Ira replied:--Thank you, but I’d rather walk.